Ingrīda Zemzare

Translated by Amanda Zaeska

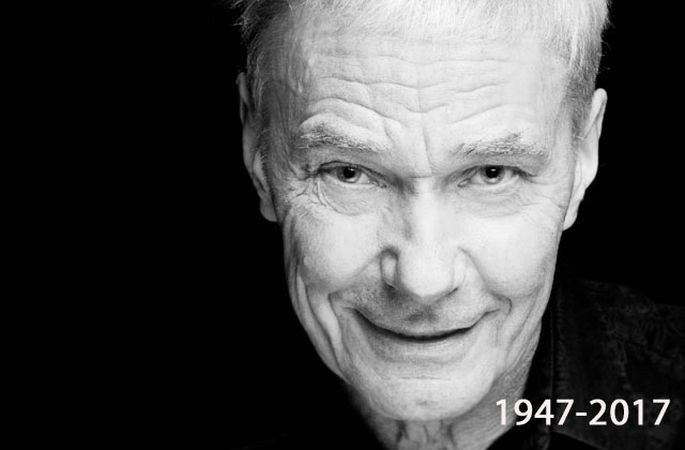

In memoriam Pēteris Plakidis (March 4, 1947 – August 8, 2017)

Pēteris Plakidis passed away during his 70th year of life. He was a superb composer and likewise a superb interpreter of the classics as well as music written by his contemporaries. He was both a poet in music and an intellectual in music, for whom music and making music was a lifestyle and the only space in which he felt able to live. He slid into the very depths of music and music making, and his contributions as a composer and interpreter of music are of equal importance. He played the solo in his own Music for Piano, Strings and Timpani, which he wrote as a youth and which was performed many times in Latvia and abroad; he founded the Transatlantic Trio together with American clarinetist Eric Mandat and cellist Ivars Bezprozvanovs and performed with them in the United States and United Kingdom; he often performed together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Maija Krīgena, to whom he dedicated some of the most beautiful works set to Latvian poetry, which continue to touch listeners precisely through Plakidis’ enduring and sophisticated music and interpretation on piano.

As Plakidis often joked, “I truly enjoy actively making music, and piano is the only instrument I more or less know how to play.” The nature of chamber music – refined feeling, a love for detail, consideration for one’s musical partners, approaching music as a living organism – dominated his thinking as a composer also when writing for symphony orchestra and choir. His choral symphony Destiny, with lyrics by Ojārs Vācietis, became an important mass for an entire era.

Plakidis entered the Latvian music scene in the 1960s and 70s, and his biography does not formally differ much from those of other composers of his age. He attended Emīls Dārziņš Music High School, the cradle for many a world-famous virtuoso. Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gidon Kremer studied there at the same time as Plakidis; Baiba Skride and Andris Nelsons were students in later years. Paradoxically, although Plakidis went on to become an acclaimed pianist, he was not accepted into the piano class, graduating from the Dārziņš school in music theory and composition instead. He then continued his studies at the Jāzeps Vītols Latvian Academy of Music (then the Latvian State Conservatoire) and rapidly made a name for himself in music. For four years while still a student, he served as the pianist for the Riga Pantomime (1966–1969), a popular avantgarde ensemble at the time. It was an interesting and creative job that inspired in the curious and artistic youth a deeper interest in the link between music and movement as well as an imaginative style of expression. It is precisely these qualities that he later cultivated in his own creative work. Alongside his internship and writing his thesis for the music academy (1970–1975), Plakidis directed the music department at the Drama Theatre (now the Latvian National Theatre) and wrote music not only for that theatre’s performances but also for other professional theatres throughout Latvia. There he honed his skills as a composer for the stage and already at a young age became one of the most serious composers of theatre and film music in Latvia, with more than fifty scores for the stage, cinema and radio plays. These were mostly intended for chamber ensemble or orchestra and were often performed live in the theatres, although his film and radio music was recorded in the studio as symphonic soundtracks. It is perhaps his work with the theatre and cinema that led Plakidis to develop a refined manner of stylisation and dialogue, which masterfully also revealed itself in his other compositions, particularly his concertos and music for chamber ensemble. The Concerto for Two Oboes and String Orchestra (1982) has been performed dozens of times, the clever Dedication to Haydn for flute, cello and piano (1982) has become a favourite among musicians, and One More Weber Opera for clarinet and orchestra (1993, commissioned for Sabine Meyer and premiered by the Copenhagen Philharmonic Orchestra [Danish: Sjællands Symfoniorkester], also known as the Tivoli Symphony Orchestra) continues to delight music connoisseurs both in concert and on Latvian Radio 3 Klasika.

In 1976 the young composer began teaching at the music academy in Latvia, where he was promoted to professor in 1991. “In my work as a pedagogue, I most of all would like to remain in the shadows. Every time I give ‘leading instructions’ to or reprimand my students, I begin to doubt myself: what right do I have in this situation to speak from my own opinion? There are, and can be, no ‘ready recipes’ in such a creative discipline as composition or instrumentation,” said Plakidis. It is no surprise, then, that in his final decade he refrained from taking on any composition students and only continued teaching the chamber ensemble class – in other words, he remained in active musical practice, where, in addition to writing scores, he had spent his whole career.

Plakidis left an extensive oeuvre of compositions for large symphonic orchestra, instrumental concertos, works of vocal-instrumental music and compositions for choir. His direct, cultivated and sometimes harsh musical expression is always a classically balanced whole – a true and specific musical message. In fact, he displayed this musical style with a vivid interplay of dialogue and characteristic harmony already at the age of twenty-two. He wrote Music for Piano, Strings and Timpani while still a student at the conservatoire, and to great acclaim at that. The composition was completed in 1969 and performed that same year at the 3rd USSR Review of Young Composers, where it earned a diploma of recognition. In a surprisingly original and contemporaneous manner, the harsh character of the Baroque themes, the principle of chaconne variations and the concerto grosso tradition reveal the worldview, fierce protest and venturous tension of a generation, resulting in a lush and diverse gallery of images. The roundness of ancient frescoes and dramatic loftiness go hand in hand with the impetuous motorics of a more modern age. The message in the piano part is very personified. The lengthy monodic piano solo at the beginning of the composition is not divided into measures. The composer’s comment reads: “In places without bar lines, accidentals apply within groups of notes beamed together.” It is like a dramatic, fully alive speech that contains within itself all of the composition’s further development – the harmonic sequences and melodic seeds from which a stirring dialogue between the soloist and the orchestra later emerges. Even more, Music for Piano, Strings and Timpani contains the rudiments of Plakidis’ subsequent individual style as a composer, which he applied very consistently throughout his entire career, from his refined chamber music to his grand compositions for symphony orchestra. Of particular mention are Canto (1986), Glance Back (1991) and Variations for Orchestra (1996), which seemingly crowns all of the composer’s conversations with his musician friends and for which he was awarded the Latvian Great Music Award, the country’s highest state honour in music. It is precisely in Variations for Orchestra that one hears the most typical features of Plakidis’ symphonic character. First of all, the equality between the soloist and the orchestra and the importance given to the principle of performance within the orchestra itself, where individual instruments and instrument groups engage in dialogue. Second, a conciseness in all dimensions, utter clarity of texture and lucidity of developing musical lines. Third, a united thematic kernel from which all of the subsequent musical material sprouts and which thematically saturates the entire texture of the composition both horizontally and vertically. This theme is often expressed as a diatonic motif.

“When I used only seven notes instead of the usual twelve, I felt as if I had gone outside into the fresh air,” commented Plakidis. “It was very enjoying to say no to chromatics, to the dissonant chromatic clusters. Pure diatonics, even if sounded all at once, even if played as clusters, nevertheless sound extremely clear. They seem to be full of air.” The initial exposition of such a diatonic motif concentrates within itself the seeds of the entire further development. One does not encounter previously determined schemes in the development of the form or drama. The music evolves according to the basic musical material, “from the original impulses that prompt the composer to pick up a pen,” as Plakidis himself explained. Such a process of creating form resembles the way a plant grows from a seed, which embodies in itself the potential for further dramaturgy and form.

Plakidis’ music is like a tête-à-tête with a person of similar opinion; the dramatic contrast between counter-forces is not a clash of two extremes but instead the difficulties of the coexistence of the ideal with less harmonious reality, which more commonly leads to resignation rather than drama. Plakidis wrote Small Concerto for Two Violins in 1991. The premiere by Aīda Grieze and Andris Pauls at the Wagner Hall in Riga was unforgettable – in that special Latvian romantic atmosphere characteristic only of Plakidis’ musical style, the two friends of the composer revealed an as yet unheard fragility and longing. Plakidis had already announced his love for a romantic strain in music in 1980 with Romantic Music for violin, cello and piano, which was also premiered, at the Latvian Academy of Music, by Andris Pauls together with cellist Ivars Pauls and the composer himself at the piano. “Neoromanticism and estrangement” is how musicologist Baiba Jaunslaviete describes the foundations of Plakidis’ music.

It is difficult to portray the music of Pēteris Plakidis. It does not submit easily. It does not pose. It lives a life of its own; it is not a portrait of the composer. Nor is it a self-portrait. If anything, perhaps it is a still life in which the depicted images are as if torn from their natural environments and arranged for a new life according to the artist’s own will – the flowers are no longer in the meadow but in a vase, the bird has been taken out of the sky and lies on the ground, the nut does not sit in its shell but between the jaws of a nutcracker. All of this is presented in relief, clearly and lushly, but from a distance, as if attempting to inspire lyricism, acuity, the sting of conflict or an almost optically visible beauty.

Plakidis’ analytical approach is defined by his manner of selection, arrangement and portrayal. And he mainly concentrates his attention not on revealing what is expressed in the portrait of a single, separate person but rather in what is universal and enduring.

The presence of an eternal quest makes the work of Plakidis classical. His style is defined by the perfection of the classical form, the principle of polyphonic dialogue and the vivid imagery that is based in the very nature of music as the art of instrumental teamwork. The dialogue principle also manifests itself in the creation of cycles – Plakidis tended to examine concepts as if looking at both sides of a coin, leading to the diptych as his favoured form of cycle.

Plakidis’ contribution is extensive and cannot be compared to that of any other, neither due to his wonderful talent nor his full, varied life in music. His vivid personality embodied an entire era in which the fraternal bonds between the composer and interpreter, between the members of a chamber ensemble, between the poet and the musicians were stronger than any other. He belonged to the “one of us” era of music, in which only talent and understanding mattered. Plakidis committed himself almost exclusively to music and making music: “My ideal is to be a servant to music. No matter the forms this service may take, it is with the greatest pleasure that I serve this mistress.”

Many notable musicians in Latvia frequently perform the music of Plakidis – his circle of friends keeps on renewing itself. Dita Krenberga, Ēriks Kiršfelds, Herta Hansena, Egīls Šēfers and his quintet. In September 2017, for already the third time (after festivals in Sigulda and Lockenhaus) and also as the composer in residence, Plakidis was invited to participate in the Kremerata Baltica Festival in Dzintari, Jūrmala. Eva Bindere and Sandis Šteinbergs played Small Concerto for Two Violins, and rising star Georgijs Osokins took Plakidis’ seat at the piano, giving completely new life to Music for Piano, Strings and Timpani. Together with Osokins, the pianist Andrius Žlabys from the United States played the invention Fifths (1976) for two pianos, which Nora Novika and Raffi Kharajanyan, the piano duo once known throughout the Soviet Union, had commissioned from Plakidis. It was for this festival that the 22-year-old Osokins first became acquainted with the music of Plakidis. And fell in love with it. Plakidis’ music lives on in concert halls and recordings, and it wins the approval of the young generation as well – a sure guarantee of longevity.