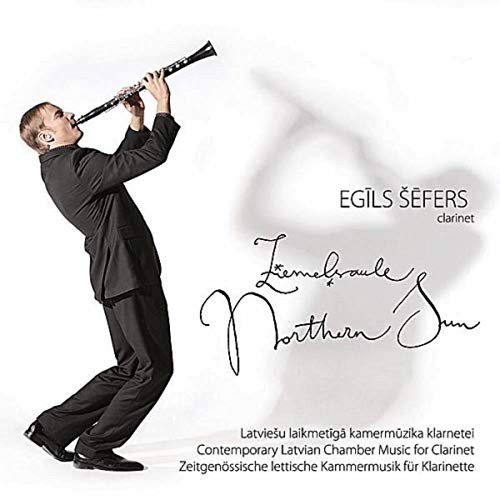

Northern Sun

Performers

Egīls Šēfers

- clarinet

Recorded

1997-2009

Release date

10.04.2010

Compositions

Description

LMIC 022

I am a proud Latvian. When I travel or perform abroad, I love to play music written by Latvian composers for my instrument, the clarinet. And I’m always delighted to answer questions about that music, and about the history and culture of my country.

The world knows very little about Latvia. Many people confuse Latvia with Lithuania, mistake the Baltics for the Balkans, and are surprised to learn that there is a Latvian language – which is not at all similar to Russian. This album is an attempt to tell about my nation, its culture and its soul. In it, I’ve displayed the range of Latvian contemporary music for clarinet – everything from solo music to quintet. I’ve also tried to show the diferent ways in which Latvian composers have approached the instrument.

I’m happy that, as a musician, I can do this by playing such a colorful and diverse musical repertoire. Like my teacher Ģirts Pāže, who once debuted the works by Imants Zemzaris and Maija Einfelde included in this album, I’ve had the chance to collaborate closely with Andris Dzenītis, Jānis Petraškevičs, Mārīte Dombrovska, and Santa Ratniece, all composers of my own generation.

In several of the pieces in this album the listener will sense a deep yearning, a desire for something unfulflled – sometimes verging on depression and loneliness. This important thread in Latvian music is particularly apparent in the works of composers such as Zemzaris and Einfelde who grew up and became professionally active during the time of the Soviet occupation. Works composed in the 1980s by these and other composers are full of inner pain and sorrow, as well as a yearning for freedom and independence. Does not Imants Zemzaris’s Balss (Voice), which is so close to our folklore, tell us about our centuries-long oppression the same way Latvian folksongs do?

In Soviet times, censorship made it impossible to criticize the regime’s Russifcation policies. These were implemented by bringing in hundreds of thousands of Russian-speaking laborers and developing industries in Latvia that were unsuited to the country’s economic and environmental capacity. In Maija Einfelde’s work Skumjās serenādes (Sorrowful Serenades), pain over the dying Baltic Sea is expressed as a lament, as sorrow – not as a protest or demand. By making Contemporary Latvian Chamber Music for Clarinet the clarinet gurgle and swoosh like polluted water, squawk like birds coated in oil, and sing a dirge for the dying sea, the composer invokes the ecological catastrophe to which this forced industrialization contributed.

The topic of ecology was one of the frst to be publicly discussed during the period of perestroika. This discussion began a process in Latvia that eventually led to the National Reawakening and the Singing Revolution and climaxed with the regaining of independence in 1991. Though Pēteris Plakidis’s Veltījums Brāmsam (Dedication to Brahms) was composed in the hopeful nineties, we can clearly discern in it the composer’s signature ability to take refuge from difcult realities in a generous dose of humor, and sometimes even an unabashed sarcasm.

Latvians of my age grew up wearing Red Pioneer scarves and learning in school about the “superiority” of Communism and Socialism and the “ideal” order of things. The early work of the composers of my generation (already embroiled in the search for identity common to all in their early twenties) refects the shock of the total downfall of this value system. Andris Dzenītis’ Arlekīna gars (Spirit of Harlequin) is a perfect example of this – the harlequin gradually transforms from a clown into an aggressive, grotesque, and almost schizophrenic madman. As he collapses, the true nature of this character (perhaps the composer himself?) is revealed – a quiet, tragic nature, heard in the voice of the bass clarinet.

The composer Jānis Petraškevičs has always searched for new ways of expression in his work. When he was composing Et la nuit illumina la nuit (And the Night Illuminated the Night) , we spent countless hours together, studying the clarinet’s alternative playing techniques and the distinct sound efects they produce. These fne nuances still fascinate him. Once, when I asked if it wouldn’t make more sense to notate a particular passage diferently (that is, in an easier way), Jānis responded, “Sometimes it’s important for me to feel a musician’s intellectual efort, the inner discomfort roused by the score.”

Santa Ratniece’s work libellules (Dragonfies) also features a search for new sonorities. Here the clarinet merges into a single whole with the low, warm tones of the cello. Even though the composer almost completely renounces a traditional musical lexicon – weaving her sound texture with quarter-tones, multiphonics, and other alternative techniques – this 2009 work also reveals the fragile, emotional, painful, and I dare say even folk-like thread mentioned earlier.

I included Mārīte Dombrovska’s opus in this album not just out of respect for her unfaltering faith in the clarinet, but also because of its special musical quality. The refned dynamic nuances and virtuoso passages in Expromptus are a challenge to a clarinetist, though a few lyrical and truly Latvian poetic sections also steal into the work. I think these are the strongest side of the young composer’s style. In them we fnd that our characteristic aching is still very real, though it is no longer the quintessential voice of an entire nation’s pain. Rather, it asks for an answer from each member of society, each confused individual – an answer which might fll the emptiness caused by collapse.

Much of the music on this album had its origin in the wounds of oppression. We who lived under that oppression experience this music in ways others cannot. While growing up, I heard Einfelde’s and Zemzaris’s works performed by my teachers with deep feeling, even tears in their eyes. But this emotionally saturated music can also bring light and hope, even when it is born of heartbreak and despair. Music, that most sensitive mirror of this age, also tells us about the unbroken spirit of our nation. It is this spirit that kept our parents teaching the Latvian language and customs to their children, regardless of assimilation attempts by the Soviet regime. Because of our unbroken spirit, Latvians kept going to church despite repression. Every four years, the entire nation united in a magnifcent song and dance festival Dziesmu svētki that brought together old and young from near and far to join in a mass choir of tens of thousands to celebrate this spirit through our songs. And at last, it was this spirit that helped us to overcome our fear and withstand intimidation by the Soviet military and helped us regain our independence.

For the conclusion of the album, I am joined by friends and colleagues from my student years in the clarinet quartet Contraverso. We have recorded a work that is very diferent from the others – Daina Molvika’s opus Ziemas saule (Winter Sun), which utilizes the broad timbral and dynamic possibilities of various instruments from the clarinet family (E-fat, B-fat, alto, and bass clarinet). This piece stands out with its expressly northern, simple, and even cold sound. The composer merely conjures up a typical Latvian winter landscape. There is no longer any sign of aching, or of the pain and sufering felt by a nation or individual, no more grieving, opposition or protests – direct or implied. I want to believe that music – this mirror – still does not deceive. I want to believe that peace and tranquility, felt in this recent work, tells us that we are at a time of healing – a time when we have taken our destiny in our own hands, when we do not regret the past or wish to shut the door on it, and when we gaze with confdence, pride, and hope into the future.

Egīls Šēfers