"Imants Kalnins, born in 1941, is a Latvian composer of classical, Rock, Pop and film music. His 7 symphonies, his Concerto for Orchestra and the Cello and Oboe Concertos, some of which were already available on individual CDs, have now been released by Skani in a box set. The music is performed by the Liepaja Symphony Orchestra. In the compositions, which he writes for the classical field, Kalnins mixes classical elements with elements of pop music to create music that is dramatic and effective and easily accessible. His Fourth Symphony, for example, may rival Mosolov’s ‘Iron Foundry.’ It is a loud experience in any case! The Fifth, on the other hand, is as different as Prokofiev’s First is from the rest of the Russian’s symphonies. The conductor of these recordings, Atvars Lakstigala, succeeds in bringing a great deal of tension to the music, contrasting the agitated, nervous passages with the soothingly quiet moments."

♪♪♪♪♪

Remy Franck

pizzicato.lu

____________________________________________________________________

"Vienmēr būs, kur rakt no jauna. Imants Kalniņš un viņa simfoniskās mūzikas kopotie raksti"

2021. gada maijā 80 gadi apritēs Imantam Kalniņam, vienam no latviešu visvairāk mīlētajiem komponistiem. Šis gads viņam iesācies ar nozīmīgiem uzmanības apliecinājumiem – 2. martā Kalniņam tiks pasniegta Lielā mūzikas balva par mūža ieguldījumu un mūzikas izdevniecība "Skani" klajā laidusi kompaktdisku komplektu ar visu Imanta Kalniņa simfonisko mūziku. Pats autors teicis, ka viņam tie ir kā kopotie raksti. Piecu disku albums ļauj izsekot Kalniņa simfoniskās daiļrades attīstībai, kas aptver vairāk nekā pusgadsimta nogriezni.

Skolas gados augu ar sajūtu, ka Imants Kalniņš ir no tiem pielūgtajiem komponistiem, kas latviešiem ir teju svētās govs statusā. Līdz 20 gadu vecumam dzīvoju Cēsīs, un vienīgā diena gadā, kad pilsētā bija sastrēgumi ar kilometru garām mašīnu rindām, bija Imantdienas. Vienu reizi pusaudža gados arī es devos paklausīties Imantdienu koncertu uz Pils parka estrādi, bet jutos kā nokļuvusi svešā ballītē, kur visi priecājas un izbauda notiekošo, bet es vienīgā neko nesaprotu. Pagāja zināms laiks, kamēr piekļuvu Imanta Kalniņa mūzikai, bet tāpat mani neatstāja sajūta, ka viņa daiļrades īpašā rezonanse latviešos man ir mīkla. Manu vecāku paaudzei, šķiet, Imanta Kalniņa mūzika nozīmējusi ko sevišķu, bet ko tā raisa paaudzei, kas dzimusi neatkarīgajā Latvijā un kuru pārstāvu arī es? Viņa simfoniskās mūzikas apkopojums radīja azartu mēģināt to noskaidrot.

"Simfonijas mūzika ir ceļš no neziņas uz harmoniju" (Imants Kalniņš)

Imanta Kalniņa septiņas simfonijas aptver laika posmu no brīža, kad komponists absolvēja Latvijas konservatoriju 1964. gadā, līdz pat 2015. gadam. Kalniņa citātu par ceļu no neziņas uz harmoniju, kas ir simfonijas mūzikas pamatā, varētu attiecināt arī uz šo septiņu simfoniju kopējo virzību, kas sākas ar skarbā īstenībā balstītu izteiksmi Pirmajā simfonijā un ved uz naivu laimīgumu Septītajā. Viņa simfoniju mūzika veras vaļā lēnām, varbūt pat neatveroties līdz galam, atstājot pēcgaršu ar daudzpunkti un noslēpumu. Komponists tajās vienlaicīgi apvieno šķietami pretējo – intensīvu, neatlaidīgu kustību, kas atgādina nepielūdzamu likteņratu, un ilgstošu, nesteidzīgu mūzikas plaukšanu. Tādējādi Kalniņš savās simfonijās radījis suģestējošu laika ritējuma un temporitma izjūtu, kas raksturīga tikai viņam.

Pirmā simfonija ir Imanta Kalniņa diplomdarbs, absolvējot konservatoriju 1964. gadā. Muzikologi te piesaukuši Dmitrija Šostakoviča mūzikas atblāzmas – katrā ziņā simfonijā dzirdamā groteska un emocionālais nospriegojums ir radniecīgs lielā krievu meistara izteiksmei. Bet cauri tai spraucas nefrizēts Kalniņš, kurš nebaidās mūzikā atklāti izpaust gan reāliju sadursmes, gan romantiskas ilgas pēc skaistuma. Ceturtās daļas izskaņā vijolēs lēni plaukst tas Kalniņa melodiskums, kas ar laiku kļūs par viņa mūzikas atslēgas zīmi un kuru latvietis atpazīs kā sev kaut ko ļoti tuvu.

Otrā simfonija tapusi gadu vēlāk. Asuma, groteskas un dramatisma te ir vairāk nekā Pirmajā, skaņdarbs ir kā pieblīvēta kolāža ar caururbjošiem muzikāliem tēliem. Simfonijā ir ļoti daudz informācijas, kas aizrauj, cērt un brīžam liek sarauties. Tāds nepakļāvīgs, spurains dadzis, kas spītīgi izslējies aizaugušas zāles vidū.

Īsts atklājums man bija Trešā simfonija, kas uzlādē ar savu stihiskumu un nepaklausīgumu. Groteska šeit vairāk ir smejoša un dauzonīga, ne tik dramatiska kā iepriekšējās divās. Viendaļīgo simfoniju ierāmē gaiša, liriska tēma, bet pa vidu komponists virtuozi spēlējas ar dažādiem laika parametriem. Te viss ņirb gar acīm kā greizo spoguļo valstībā, te pēkšņi viņš sastindzina laika ritējumu ar ilgstoši izturētu akordu klasteri, no kura negaidīti izlien fagota vientuļā balss. Enerģiskais ritma "draivs" nedaudz atgādina Igoru Stravinski, un man ārkārtīgi patīk brīži, kad latviešu mūzikā ieskanas šī stihija. Simfonija apvieno jauneklīga eksperimentētāja garu ar meistara spēju īstenot lietu kārtību, un acīmredzot tāpēc Trešā simfonija šķiet tik pievilcīga.

Plaukšana un laimība

Imanta Kalniņa Ceturtā simfonija, dēvēta arī par roksimfoniju, ir hrestomātisks opuss latviešu mūzikā. Pats komponists Māra Čaklā grāmatā "ImKa. Imants Kalniņš laikā un telpā" par to ir teicis šādus vārdus: "Tā ir enerģijas, dinamiskas enerģijas pārpilna, manuprāt, viņa manifestē ārkārtīgi dinamisku enerģijas kondīciju. Attiecību pret pasauli. Optimismu, tas ir par daudz abstrakti teikts, bet viņa ir absolūtas dzīves enerģijas aktivitātes pārpilna. Attiecība pret pasauli. Gaiša attiecība."

Toties Ingrīda Zemzare grāmatā "Jauno mūzika" Ceturto simfoniju raksturojusi kā "psiholoģiski smalku un konkrētu savas paaudzes portretējumu". Es gan nepieredzēju dzīvi Padomju Savienībā un atkušņa laikus, bet šī simfonija būtiski iekustina arī kaut ko manī, jo tā ir ne tikai par nostāšanos pretī konkrētai laikmeta iekārtai, bet galvenokārt par cilvēka gribu un plaukšanu pretī kam īstam. Laikam tieši šis faktors ir tas, kas tik ļoti trāpa sirds centrā, ne tik daudz rokmūzikas un dziesmas klātbūtne, kas simfonijā vairāk kalpo kā izteiksmes paņēmiens. Šī simfonija, līdzīgi kā Jura Podnieka filma "Vai viegli būt jaunam?", ir viens no tiem mākslas darbiem, kas, portretēdami konkrētu laiku, reizē runā par mums visiem. Jo pēc šīm vērtībām – iekšējās brīvības un īstuma – cilvēki alka gan šo darbu tapšanas laikā, gan alkst arī šodien, mūsdienu kapitālismā.

Piektā simfonija ar savu augsto vispārinājuma pakāpi, apjomu un satura dziļumu, iespējams, no visām septiņām simfonijām visvairāk iemieso simfonijas žanra kvalitātes tās klasiskajā izpratnē. Andris Vecumnieks Latvijas Radio 3 "Klasika" raidījumā "Post factum" Piekto nodēvēja par Imanta Kalniņa simfoniskās daiļrades virsotni. Savā izteiksmē tā noteikti ir abstraktāka un objektīvāka nekā Ceturtā, bet tai piemīt metaforisks virsslānis un iekšējais briedums, ko noteikti novērtēs īsti simfoniskās mūzikas gardēži. Šī simfonija turpretim plaukst pretī tādam kā filozofiskam piepildījumam, un tas notiek ilgstoši, nosvērti un neatlaidīgi.

Sestajā simfonijā tiekšanās pēc skaistuma un garīgas mīlestības jūtama pat vēl vairāk nekā Ceturtajā un Piektajā. To vistiešākā mērā atklāj kora dziedātie Rabindranata Tagores un Bībeles teksti otrajā un ceturtajā daļā. Par to, kā komponistam konkrēto vēstījumu izdevies īstenot simfonijas cikla ietvaros, varētu strīdēties. Šī simfonija, manuprāt, ir saistoša ar atsevišķiem fragmentiem, nevis kā procesuāla, četrdaļīga simfoniska celtne. Otro un trešo daļu es varētu klausīties kā patstāvīgus skaņdarbus, jo kalniņiskais skaistums un dzīves enerģija tur plūst pāri malām.

Pēc pirmatskaņojuma 2001. gadā simfonija saņēma kritiķu nopēlumu. Gaidas no komponista, kas radījis tādus opusus kā Ceturtā un Piektā simfonija, acīmredzot bijušas visai augstas, un, nesadzirdot gaidīto, loģiski, sekoja vilšanās. Pieņemt kaut mazāko neizdošanos no autora, kas iepriekš uzrakstījis meistardarbus, laikam ir daudz grūtāk. Varbūt skanēs dīvaini, bet mani savā ziņā aizkustina, ka arī pašiem izcilākajiem autoriem kaut kas nesanāk. Jo tas viņus vairāk padara par cilvēkiem un noceļ no dievišķotajiem augstumiem, kuros mākslas radītājus esam ielikuši bez viņu pašu piekrišanas.

Te man nāk atmiņā epizode, kad pirms sešiem gadiem Vīnes "Konzerthaus" klausījos 2009. gadā uzrakstīto Arvo Perta skaņdarbu "Silhouette", kas veltīts Gistavam Eifelim un kuru spēlēja Parīzes filharmoniskais orķestris Pāvo Jervi vadībā. Es cerēju sagaidīt to Pertu, kurš savos izcilākajos darbos man dāvāja tik nozīmīgu pārdzīvojumu, un neapzināti to meklēju arī šajā skaņdarbā. Bet te – tik vien kā neizteiksmīga mīņāšanās pa skaņām savā iecienītākajā tehnikā un ne miņas no tā Perta, kas man bija tik svarīgs. Biju no tiesas vīlusies, bet tā jau bija vilšanās manis pašas gaidās, nevis viņa veikumā. Komponista daiļrades process notiek neatkarīgi no tā, ko sagaida publika un kritiķi, vienīgi – vai mēs spējam par to reflektēt kā par dzīvu, allaž mainīgu procesu, kur neizdošanās ir daļa no īstenošanās, vai lūkoties uz to tikai no savu ekspektāciju un prasību prizmas?

No Septītās simfonijas strāvo pozitīva naivisma gars. Tā ir ļoti slidena stilistiska, kurā rakstīt, gandrīz kā pārvietošanās pa naža asmeni. Ja izdodas noturēties un trāpīt mērķī, var sanākt mocartisks, dievišķi tīrs skaistums, ja ne – tas var izklausīties pēc kaut kā banāla un primitīva. Diemžēl Kalniņš šeit vairāk ir netrāpījis, nekā trāpījis, vismaz manām ausīm simfonija lielākoties izklausās pēc lauku sādžas mūzikas ar neveiklām dejām un maršiem. Taču autora iecere ir nolasāma ļoti skaidri, it kā viņš būtu mērķējis uz kādu absolūto harmoniju un laimīgumu.

Koncerti un miniatūras

Koncerts simfoniskajam orķestrim ir Kalniņa 60. gadu opuss, kurā komponists, šķiet, eksperimentējis ar dažādiem instrumentu spēles paņēmieniem, tembriem un to kombinācijām, kas kļuvuši par kolorītas izrādes tēliem. Mūzika svilpj, griež un mēdās, sitaminstrumenti rībina pirmatnēju deju, kuru pēkšņi nomaina Kalniņa liriskā un liegā puse. Sapratu, ka mans pārsteidzošākais atklājums Imanta Kalniņa simfoniskajā daiļradē tomēr ir tas spēks, kas ir miesisks, nepieradināts un "šauj pa taisno". Un tā viņa simfoniskajos darbos ir daudz.

Koncerts čellam ar orķestri rakstīts vēl studiju laikā, no šī darba dveš meklējumi, cēla melanholija un rezignācija. Bet 49 gadus vēlāk komponētais koncerts obojai atrodas turpat, kur Septītā simfonija, – utopiskas laimības pasaulē. Vai šajā gadījumā personīgu un subjektīvu laimes hormonu ir iespējams pārtulkot skaņās tā, lai tas aizsniegtu arī citus, – par šo jautājumu domāju, klausoties Obojas koncertu, bet atbildi neguvu.

Albumā pārstāvētās miniatūras, mūzika filmai "Pūt, vējiņi" un kompozīcija "Santakrusa" no abām pusēm ierāmē iespaidīgo, sešas stundas garo mūzikas apkopojumu un atspoguļo Imanta Kalniņa spožā melodiķa un dziesminieka pusi, par kuru latvieši viņu tā mīl. "Domāju, ka dziesma ir vispilnīgākais mūzikas veidols. Mūzika pašos pamatos ir radīta dziedāšanai," tā Imants Kalniņš saka grāmatā "Jauno mūzika".

Imanta Kalniņa simfoniskās mūzikas apkopojums man deva iespēja ieraudzīt komponista daiļrades mantojumu objektīvāk, bez idealizācijas, kas latviešiem mēdz piezagties attiecībā uz savām kultūras ikonām, kā arī atklāt fascinējošas viņa mūzikas šķautnes, kas līdz šim bijušas svešākas. Tāpat atkal atdūros pie sen zināmās patiesības, ka mēs par t.s. "slavenajiem klasiķiem" īstenībā zinām daudz mazāk, nekā mums pašiem šķiet. Tur vienmēr būs, kur rakt no jauna.

Lauma Malnace

_________________________________________________________

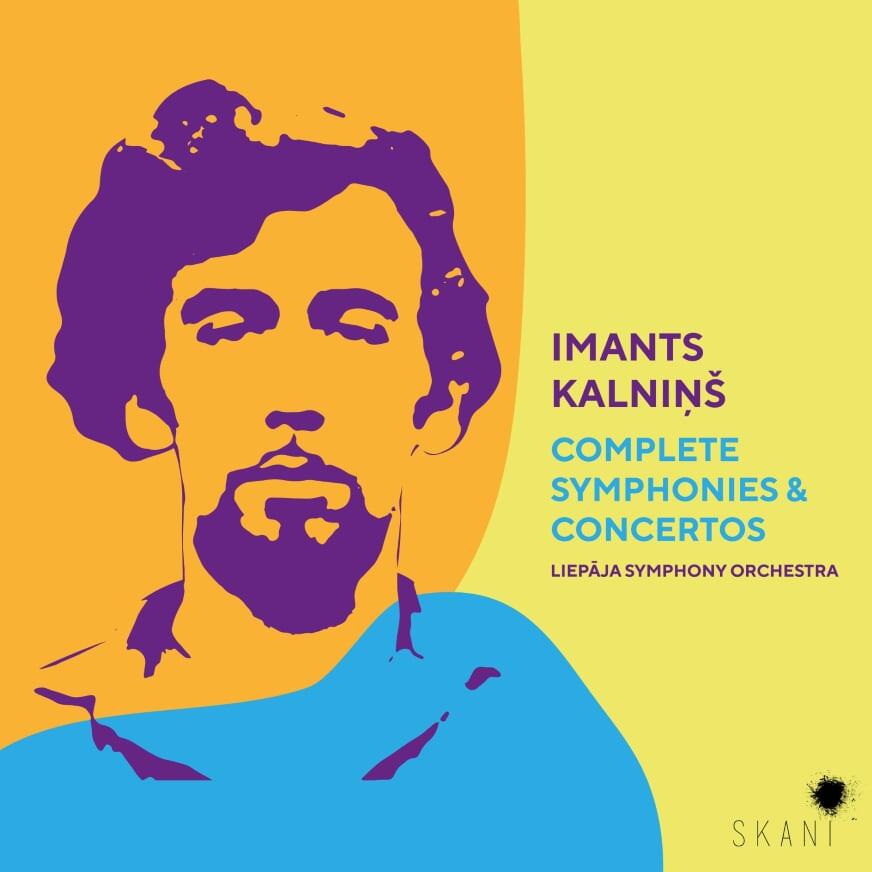

"It must come as something of a shock that Imants Kalniņš, the Rock-meets-Classical enfant terrible of Latvian music, is 80 years old this year. Skani doesn’t draw attention to this in any noticeable way in this box set of his largely previously-released discs, though they do contrast the hairy-faced youngster – every inch looking like a grizzled if impish member of The Soft Machine – alongside his more contemplative older self.

Three of the seven symphonies with associated works have been reviewed before (review ~ review) and I am going to cast a relatively deft pen over what you can expect to find if you are new to the composer. His compositional omniverousness was allied to a politicised stance but he had a notably fine ear for direct influence. In his First Symphony (1964), for instance, the most explicit influence is Shostakovich – the winds are piercing, the syntax is frequently tersely sardonic and there is a truly martial sense of drama. The slow movement is drenched in colour and texture in music of ambiguous expressive meaning. But he is no mere epigone; the finale is controlled, architecturally sure and the music propulsive, with vibrant brass and percussion to the fore. The following year came the Second Symphony and signs of that ability to absorb, rapidly, and equally rapidly to project disconcerting strata of so-called musical hierarchies – the sinewy with the demotic, the high with the light. Thus, the opening jagged procession of mosaic-like material leads to a slow processional that then turns into strangely Light Music (the capitalization is here appropriate; it really does sound like this). In the central movement the curt is juxtaposed with the dreamlike, the lyricism emerging all the more expressionistic for this sense of destabilization. If one senses Mahlerian shadows in the finale there are also Rock-influenced ones too – and this was written some years before the Fourth Symphony that was really the ‘Rock’ Symphony. Influence and means pile up – he is not above some neo-classicism either.

In 1968 Kalniņš wrote Symphony No 3. His goal, increasingly, was communication. He had played keyboards in a Latvian Rock group and was always open to the more expansive possibilities of popular music in general. Whatever happened in the three years between Symphonies 2 and 3 the result was startling. The new work, cast in a single span composed of five sections, was the epitome of the light and balletic. In its communicative resourcefulness it seemed to look back to Prokofiev and in its quietly neo-classical elements Stravinsky was a model. There’s a post-Honegger symphonic chugging power. The last influence, if such it was, was both lively and astute given Honegger’s far-too overlooked set of symphonies. Thence, then, to the Fourth, which is what I think we should call his Rock Bolero symphony (the Bolero rhythm was to reappear several times as the cycle developed). This is performed with magnificent control by the Liepāja Symphony Orchestra under Atvars Lakstīgala who directs the first five symphonies: Māris Sirmais takes over for the final two, the Oboe Concerto and Santa Cruz. This is his second longest symphony at 49 minutes – only No 6, at an hour’s length, exceeds it. The opening generates a propulsive rhythm, whilst the slow movement sets up a kind of Pizzicato Pavane, and has warm, filmic episodes, whilst also exuding a benignly phantasmagoric quality that admits the childlike. This shouldn’t be surprising. The music combines two elements at which he was excellently equipped; contemporary Rock and writing film scores. There are hints of minimalism in the vivid writing and the finale is overtly Pop-Rock, the music being songful and strident. This was largely imposed on the composer by the Soviet authorities who wouldn’t stand for actually sung poems by the American Kelly Cherry. So, the songs were transposed for the wind instruments and that’s the form in which the work is performed here. You will note the bass guitar and drums feeding the Rock machine throughout the symphony.

There was a six-year gap until Symphony No 5. The music’s terseness and quietly sombre nature reflect back on his first two works in the genre. He also makes much of a sequence – variations in effect – of scenes both withdrawn and dramatic. There’s a sense of a developing fugato – there is contrapuntalism in one’s ear when listening to much of his music – in the festive Scherzo-like third movement, whilst the finale employs a Latvian folk song, partly wrapped in Nordic shimmering strings and eloquent wind soloing. Grandeur, too, before the gently quiet ending. If the Fifth Symphony tacitly acknowledged that the Fourth had left dilemmas instead of solutions, then the fact that No 6 followed fully 22 years later is some kind of answer. His first symphony of the new millennium it triumphantly reintegrated his fondness for ostinato, for auburn-textured winds, and dappled sonorities. There are again Bolero hints though never in so defiant or so glorious a way as in No 4. Rather they are now part of the music’s inner fabric. The second and fourth movements employ a mixed choir. Kalniņš selected love poetry from three of Tagore’s collections, setting them in such a way that syncopation conveys a sense of off-beat rhythms; music of gentleness and refinement, with the most precise of instrumental touches that point to the music’s Indian origins. In the finale he sets a prayer to Christ. Cumulatively the music draws to itself an incremental sense of spiritual beauty and the close, very beautiful and rather remarkable in its freedom from conventional bombast, ends quietly, another feature of his symphonic music that shouldn’t be overlooked.

Symphony No 7 dates from 2015. Perhaps, in its frank reminiscences of film music from his youth, this may seem a rather touching envoi to the symphonic form. But that would be to reckon without those esoteric touches to show that something else is going on. There are March themes, some ‘Eastern’ sonorities that began to appear in his later symphonies, exciting motifs that generate Shostakovich-like drama, as well as Bolero underpinning of filmic warmth, something that is contrasted with slower, gauzy orchestration. Rather, then, than a fond farewell this is an altogether more active symphonic construction, one that binds elements of his musical writing for over 50 years and presents them as a lifetime’s work.

When some of these recordings were first issued some came with other orchestral music. The Fourth Symphony, for example, shares disc space with the contemporaneous music to the finale of the film Pūt, vējiņi – powerfully augmented by an electric guitar solo played by Māris Kupčs. The Cello Concerto is his earliest work here, dating from 1963 when he was in his very early 20s and in his third year of studies. It’s a bipartite work, melancholy and yearning, that doesn’t promote much contrast but ends in calming neo-classical gentleness. The Oboe Concerto is a different kind of piece that exploits the solo instrument for curlicues of folkloric richness as well as tuneful elegance in the finale. I have to part company with the notes (which are very good and in Latvian and English) which find the work juxtaposes ‘the skewed and destructive sides of life with pure beauty and unsullied harrmony’. I certainly get the latter – this is, to me, in effect, a pastoral idyll - but I don’t find the former; at least not in this work. It’s certainly a component of some of his other music. The Concerto for Orchestra (1966) seems to explore the virtuous triumvirate of Shostakovich, Honegger and Bartók as well as opportunities for percussion-tattered solos, à la jazz. The ending is decidedly brusque. Santa Cruz is a gentle, brief theatre entr’acte.

This ends an absorbing symphonic life. It charts the career of a composer unwilling to accept the status quo and yet not prepared to break the formalities of symphonic conception. Kalniņš sought the best means by which to convey his musical message – of plurality without puerility, of openness without offering open season to every fad and fashion. He absorbed Rock and some of the freedoms of jazz, anthemic music and Indian love poetry; he rejoiced in lyricism and contrasted it with the bitter constraints of societal pressures as mediated musically via the corrosive and battering Marches that reappear time and again in his symphonies.

Dating of the recordings isn’t exact, the booklet merely noting the generic dates of recording as the period between 2014 and 2020. No praise is too high for the heroic orchestra and interpreters – primarily Lakstīgala because he shoulders most of the works but Sirmais too should be saluted for the ways in which he brings to life the Sixth and Seventh symphonies; no small achievement.

Perhaps it’s right that the colourful box – green, orange, blue, purple - should take us back to the primary-coloured sixties when this brave and resourceful composer set his face against conformity but also against the mechanical blandishments of the avant-garde, obscurantism and academic provincialism."

Jonathan Woolf

MusicWeb

_________________________________________________________

If the eye-catching box design doesn’t attract your attention, the first track on CD 1 will, an extract from the veteran Latvian composer Imants Kalniņš’s 1973 score to the popular Latvian film Blow, Wind. Based on a folk song and lushly orchestrated, it could pass for a slice of Vertigo-era Bernard Herrmann, at least until the electric guitar solo starts. It makes for a perfect appetiser. Skani haven’t arranged Kalniņš’s seven symphonies in chronological order, so to hear his 1964 Symphony No. 1 you’ll have to switch discs. A sombre, large-scale work owing a debt to Shostakovich, the gaudy, ambiguous apotheosis both chills and thrills. Kalniņš' gift for widescreen melody asserts itself again in the follow-up from a year later. At times you’re reminded of Malcolm Arnold. Spikiness and sweetness co-exist, as when the slow movement’s austere chorale segues into a melting flute tune.

Symphony No. 3 is smaller in scale and quirkier, supposedly prompted by Kalniņš’ colleague Arvo Pärt suggesting that he compose “the craziest thing he could think of” and producing a sequence of five pungent, balletic miniatures. There’s some brilliant percussion writing in a 1966 Concerto for Orchestra, composed shortly before Kalniņš founded the band 2XBBM, playing keyboards until state interference forced the group to split. There’s a selection of their songs on YouTube, and a recycled 2XBBM ballad appears in the opening movement of Symphony No. 4, accompanied by electric bass and drum kit. Kalniņš’s finale originally set texts by US poet Kelly Cherry but the Soviet authorities refused to sanction a performance until an instrumental transcription was provided. It’s a bold, accessible work, played with punch and panache by the Liepāja Symphony Orchestra under Atvars Lakstīgala, sharing conducting duties across the cycle with Māris Sirmais.

No. 5 begins with dark, restless energy and closes in a mood of chilly resignation. Over 20 years separate it from its successor, during which time Kalniņš became involved in the push for Latvian independence and was elected to the state parliament in the early 1990s. Symphony No. 6 is an epic musical response to Latvia’s recent history. The two choral movements contain some exquisite music, but the work feels overstretched. No. 7, completed in 2015 is concise, lyrical and engaging. Kalniņš’ Cello and Oboe Concertos, both enjoyable, are thrown in, plus an appealing miniature written in the same year for a Latvian National Theatre production. I’m now a fan – it’s a treat to encounter a hitherto unknown composer with such a distinctive and likeable personality. I’ve been dipping in and out of this box for months, and I’m still discovering things to marvel at. The performances are committed and beautifully recorded. A winner.

Graham Rickson

www.theartsdesk.com