Maija Einfelde hails from Valmiera in Latvia, and began her music studies with her mother who was a church organist. Her education continued at Alfrēds Kalniņš Music School in Cēsis, then at Jāzeps Mediņš Music College in Riga. In 1966 she enrolled at the Conservatoire in Latvia and there studied composition with Jānis Ivanovs. Following graduation she took on several teaching posts in theory and composition at the Alfrēds Kalniņš Music School in Cēsis, Emīls Dārziņš Music College and Jāzeps Mediņš Music College. Her big break came in 1997 when she secured victory at the international Barlow Endowment for Music Composition Competition in the United States. Since that time, she has been the recipient of several awards. Her compositions mainly centre on choral and chamber music. The three Sonatas for Violin and Piano span a period of ten years between 1980 and 1990, with the Solo Violin Sonata penned in 1997.

Written in 1980 and premiered in 1981, the Sonata No 1 for Violin and Piano is structured in four movements. The first is a Recitativo which is improvisatory in character. Spiky and angular, Einfelde employs pizzicatos and harmonics to powerful effect. More energy is generated in the second movement, where the thrust is resolute. An ostinato bass, at one point, gives the music forward propulsion. The slow movement is marked Mesto. Its static quality generates a feeling of glacial stillness. The finale is one of verve and vigour.

Five years later came the Second Sonata. There are only three movements this time. It opens dramatically, described by the composer “like a window thrown open”. Gradually, the music becomes more introspective. The second movement is a beautifully constructed minuet. In the final movement, the piano is left to its own devices in the opening measures. The violin eventually enters, playing a long flowing line against a bubbly piano accompaniment. Then there are swirling scales on the violin, before the movement ends with "the clock of the soul-tick-tock".

In the third Sonata (1990) there are only two movements. In the first, more substantial at just over 10 minutes, the composer directs the players to play “as slow as possible”. The music has a mesmeric effect and builds to a forceful climax. The tension that has built up is relieved by the Adagio second movement, which acts as a consoling balm.

It was another seven years before Einfelde composed her three-movement Sonata for Solo Violin. She regarded her ideal as Bartók’s Violin Sonata No 2 and his Solo Violin Sonata. With regard to the latter, she states “I have not consciously stolen anything…….”. The first movement is an Adagio, furnished with long-breathed chords. The middle movement is an animated allegro, barbed and serrated. The work ends with a static mesto.

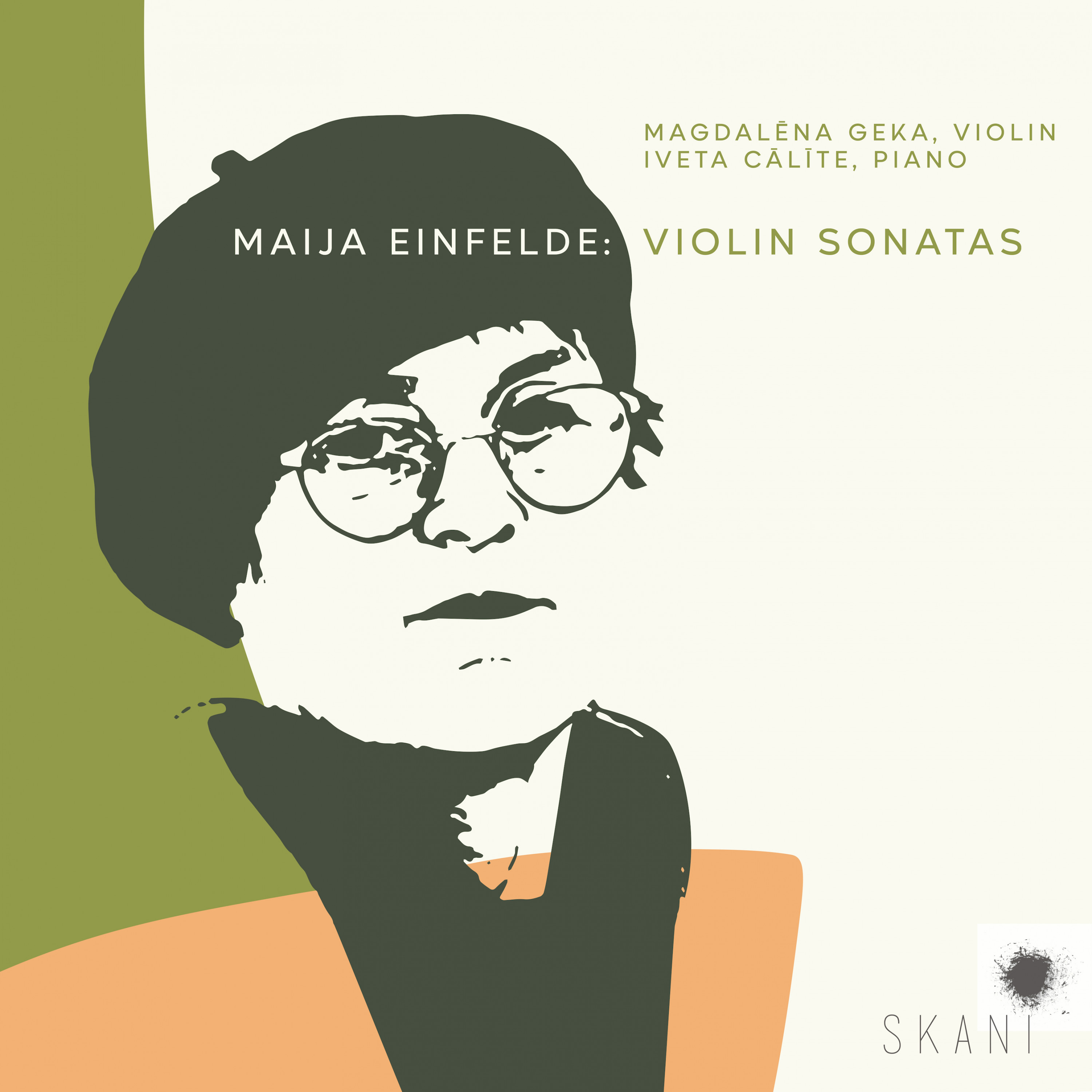

I applaud Magdalēna Geka and Iveta Cālīte for their pioneering spirit in recording these works, which merit greater currency. The liner notes, in English and Latvian, provide sufficient background information. The performances benefit greatly from Skani’s superb engineering. This release is well-worth exploring.

Stephen Greenbank, 12/2021

Musicweb International

________________________________________

If art does not always imitate life, it can certainly echo it. For a case in point, then look no further than the Latvian composer Maija Einfelde (born 1939). As the liner notes to this release make clear, Einfelde has endured a complicated and rather winding path to the widespread acceptance of her compositions. A difficult childhood often away from her parents, then not seeing eye-to-eye with her professor at the Latvian Conservatory of Music, followed by disputes with the Composers’ Union during the Soviet years when they did pretty much everything they could to thwart her creative spirit are just three instances of obstacles that had to be overcome.

In the Latvian context, Einfelde’s three sonatas for violin and piano, plus a further sonata for solo violin, constitute an important contribution to the genre. Listening to this recording from beginning to end, a repeating characteristic jumps out – in a word, it is edginess. That is not to say that it present in every movement – if that was the case the music would risk being just one oppressive page after another, which is not the case at all. But edge is definitely central to Einfelde’s idiom, and to go back to where I began, perhaps that’s only to be expected.

The first sonata, from 1980, is in four brief contrasting movements. The first is free-flowing yet has that edge in her use of harmonics, the second is more emphatic, the third is stuck in stasis and the fourth has a yearning character.

The second sonata, written in 1985, condenses the form to three movements. The opening movement starts with dramatic flourish before it looks inwards and becomes more pensive. The middle movement is a somewhat unexpected Minuet, scored with delicacy and consummate technical knowledge. The closing movement initially appears to be a piano solo, but once the violin joins proceedings the music proceeds with amiability. This might have captured – one conjectures – a moment of rare peace for the composer.

The third sonata, from 1990 in two movements, brings forth that edginess again. This time, it takes a different form. The first movement, played as slowly as possible, creeps inexorably to a heated pitch that excites and disturbs in equal measure. The second movement contrasts, thankfully, with a more peaceful aspect.

The solo sonata, from 1997, has Bartok’s Second Violin Sonata as its model, as Einfelde held it to be an ‘ideal’. Of the three movements the middle one is the most demanding for both player and listener – at times one might think the violinist is playing razor wire rather than strings, such is its all-encompassing forcefulness. This goes some way beyond mere edginess.

The violinist Magdalēna Geka and pianist Iveta Cālīte prove fully up to the demands of this music, both technically and in terms of its spirit. The recording is first rate, proving that Latvian music is in safe hands with the Skani label. Bring on further releases, and soon, as many treasures of the Latvian repertoire deserve a wider audience.

Evan Dickerson. 09/02/2022

evansupbeatmusic.blogspot.com

________________________________________

Every now and then there is an album that is simply captivating, the music so powerful that one feels the need to go back to it over and over again. This particular album of sonatas by senior Latvian composer Maija Einfelde (including world premiere recordings of the third sonata and a solo work) had that special effect on me. The three sonatas for violin and piano and one for solo violin were written over the span of the last 20 years of the 20th century. They do not feature any exuberant contemporary violin techniques (though the imitation of the clay bird whistle sounds in the second sonata is delightful) but rather share some similarity with the musical language of Messiaen. What they do feature is an abundance of darkness, shades of deep sonority, profoundness of the life lived and an encompassing artistry. This music is supremely focused, there is no note that is unnecessarily placed, and maintaining this sort of conceptual intensity requires both fortitude and heart from the performers. Violinist Magdalēna Geka and pianist Iveta Cālīte have both. These two powerhouses delve deeply into the music of Einfelde, as if their lives depend on it. Geka’s tone is so resonant, so intense and clear (especially in the high register), that one feels its reverberations in the body. What is most 50 | March 4 – April 15, 2022 thewholenote.com impressive is that both artists found a way to add another dimension to Einfelde’s music – joyful, triumphant moments between the waves of darkness. And this is the way that magic happens.

Ivana Popovic,

The Whole Note, VOLUME 27 No 5, 03-04/2022